Fieldwork on Mograt island

Fieldwork on Mograt island

The 2008 field season

The H.U.N.E. campaign 2008 took place from 26 January to 5 April, it was financed by the Packard Humanities Institute (PHI). The 2008 field season involved archaeological work at the Fourth Cataract, on Mograt and at Musawwarat es Sufra in the Butana. The team obtained permission to undertake archaeological work in the H.U.N.E. concession area in the Dar al Manasir at the Fourth Cataract from the Higher Manasir Committee in Khartoum before leaving for the field. H.U.N.E. was also invited to the research area by the Local Manasir Committee. However, these permits were revoked after only a few days of fieldwork, and the H.U.N.E. team was asked by the Manasir to leave the concession area immediately.

As in 2006 H.U.N.E. then continued work on Mograt island upstream of the Fourth Cataract. Mograt is the largest of the Nile islands, which is also threatened by dam building activities and engineering projects linked to an expansion of agricultural activities. The rock art team, relocated to Musawwarat es Sufra in the Butana, where it focused on recording the exceptional corpus of ancient graffiti at the Meroitic Great Enclosure. This site was selected for detailed study, as it provides close parallels to the rock art in the H.U.N.E. concession area at the Fourth Cataract, and especially to the rock art corpus of Us island.

Fieldwork on Sur island, Fourth Cataract

1. Excavation of Neolithic and Kerma period settlement sites

After completing the archaeological survey on Sur in the 2007 season, a general overview of the chronological and spatial distribution of sites in the island became possible for the first time (see H.U.N.E. 2007). Among the most striking features was a group of seven settlement sites ranging from the Neolithic to the Kerma period (c. 5000 – 1500 BC). Given that only little evidence on such sites exists throughout the whole Fourth Cataract area and beyond, the sites on Sur were chosen for further study. A first objective of this season’s work was to excavate small test trenches at each of them in order to determine which of them should be investigated at a greater scale. After two days of work, sites SR050 and SR056 had been tested by 0.5 m x 1.5 m trenches. While the four trenches at SR050 were very poor in terms of archaeological material, a different picture emerged at SR056. There, substantial amounts of pottery sherds and stone artefacts of all positions in the chaine opératoire as well as parts of clay structures had been found. Unfortunately, after these important finds had come to light by the third day of the excavation, all work had to be stopped due to political problems.

Excavation team: Reinhold Schulz, Björn Briewig, Alexandra Bergmann, Philipp Georges, Fawzi Hassan Bakhiet.

2. Excavations within the church SR022.A

A second main objective of the season was to further investigate the individual components of the complex medieval site SR022 in order to gain more data on its composition and function(s). Work started at the church SR022.A, which had been to a large part excavated already in the previous campaign (see H.U.N.E. 2007). In the first two days, some open questions concerning its architectural features could be settled. Excavation of a suspected grave in the interior of the church began, but had to be aborted at the request of the Manasir.

Excavation team: Daniela Billig, Andrea Schlickmann, Petra Weschenfelder, Tim Karberg, Ralf Miltenberger.

Map of Mograt island, produced by the geographical subproject of H.U.N.E. 2008, with an indication of the investigated archaeological sites

1. Palaeolithic finds at MOG064

The first survey on Mograt in the H.U.N.E. campaign 2006 (see H.U.N.E. 2006) had already revealed an unusually high concentration of Palaeolithic stone artefacts on the surface in the vicinity of the modern village of Karmel in the upstream part of the island. One main aim of the 2008 campaign was to determine whether there is a possibility of finding Palaeolithic material not merely on the surface but also in stratified levels. This was considered especially important in view of the fact that such finds are very rare in Sudan, potentially implying a major contribution to the knowledge of the country’s archaeology. At site MOG064, situated on the desert plateau east of Karmel, we noted not only substantial numbers of Palaeolithic artefacts, but also a considerable depth of sediment, visible in some recent pits dug by the local population for the extraction of pebbles. Thus, an excavation of 16 m2 was opened next to one of those cuttings. An upper stratum contained finds of mixed date, such as sherds of Christian, Kerma and Neolithic or Mesolithic age as well as stone artefacts. Below it, a second layer contained sherds and stone artefacts that were exclusively of Mesolithic or Early Neolithic date. This assemblage was followed by a third stratum containing only Palaeolithic stone artefacts. The finds recovered in the small-scale excavations of both these prehistoric strata still need to be studied in detail, but it is expected that they will offer interesting insights into these hitherto little known phases of Nubian prehistory – and they certainly underline the potential of MOG064 and the island of Mograt in general for the study of these periods.

Survey team: Reinhold Schulz, Björn Briewig, Alexandra Bergmann, Philipp Georges

Site MOG064 before excavation.

Site MOG064 before excavation.

Lithic artefacts from the early Neolithic or Mesolithic layer at MOG064.

Lithic artefacts from the early Neolithic or Mesolithic layer at MOG064.

Palaeolithic artefacts at MOG064 in situ.

Palaeolithic artefacts at MOG064 in situ.

2. The Kerma cemetery MOG034

During the first H.U.N.E. survey on Mograt in 2006, several cemeteries of possibly Kerma date had been recorded. Given that they would be the most upstream example of Kerma burials known so far, one of these sites was chosen for further investigation in 2008. MOG034 comprises 11 graves with tumulus superstructures. The largest feature, no. 1, with a diameter of c. 16 m, was investigated in detail. The flat tumulus, itself built of dark grey basalt rock, was covered with a decoration of quartzite rocks and brown flint pebbles. Unfortunately, the burial had been thoroughly robbed, most probably during the Christian period. Potsherds of Kerma and Christian date were recovered in the central area of the tumulus surface. Of the original internment, merely the pelvis was found in position. Of the grave goods, a fragmentary bowl was preserved. Its form and decoration indicate a Middle Kerma date (c. 2050 – 1750 BC). The architectural features of the tumulus need to be assessed in further comparative studies. However, it appears that this type is absent or rare in the nearby Fourth Cataract region, indicating that the island of Mograt might have been in closer relation to the core region of Kerma, at the Third Cataract, than with its surrounding territories.

Excavation team: Reinhold Schulz, Björn Briewig, Alexandra Bergmann, Philipp Georges

Monumental Kerma tumulus, feature 1, at MOG034.

Monumental Kerma tumulus, feature 1, at MOG034.

Aerial view of tumulus MOG034, feature 1.

Aerial view of tumulus MOG034, feature 1.

Distribution of white and yellow pebbles, of bones, ceramics and lithic artefacts at MOG034, feature 1.

Excavation of the burial structure at MOG034, feature 1.

Excavation of the burial structure at MOG034, feature 1.

Fragmentary bowl of Middle Kerma date from MOG034, feature 1

Fragmentary bowl of Middle Kerma date from MOG034, feature 1

3. Fortress MOG048

In the very west of Mograt, a fortress is located near the village of Ras al-Jazira (“head of the island”). It had already been visited in the 2006 H.U.N.E. survey. During the current campaign, a detailed ground-plan of the structure was produced. In accordance with local topography, the fortress is only roughly rectangular, about 65 m long and at its maximum 60 m wide, with bastions in the corners. The northeast bastion is still preserved up to a maximum height of 8 m. The enclosure walls of the fortress are 4 to 5 m thick. The eastern one has an outer stone facing protecting the mudbrick interior; halfway between the two corner fortifications there is a further massive bastion. The northern wall consists of heavy mudbrick with interior and exterior outer stone facings. The fortress is entered through a main doorway in the northern wall, protected by a bastion or tower in front. Smaller gates in the northern and eastern walls appear to be later additions, as do the outworks in the same area areas. No walls were visible in the west and south in the absence of excavation, but the southwest bastion could be identified. On the eastern side, facing the island’s interior, the outer defences of the fortress are partially preserved. Some meters outside the eastern outwork, a trench is still noticeable along the outer wall. A ring of upright pointed stone slabs in front of this trench may have served as a defensive structure to deter attacking cavalry. The interior of the fortress MOG048 contained no standing walls, but was scattered with stone slabs, fired bricks and medieval ceramics. The ground level of the northern part was relatively high. This fostered the hope to find preserved walls or at least foundations underneath. Therefore, excavation in this part was deemed promising.

Excavation team: Daniela Billig, Andrea Schlickmann, Peter Becker, Tim Karberg, Ralf Miltenberger, Fawzi Hassan Bakhiet

Northeastern bastion of the fortress MOG048

Northeastern bastion of the fortress MOG048

Defensive installation of upright stone slabs at MOG048.

Defensive installation of upright stone slabs at MOG048.

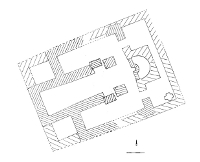

4. The church at MOG048

One main enterprise of H.U.N.E. 2008 was the investigation of a Nubian church in MOG048. Although only the southern half of the building could be uncovered in the time available, several architectural features and evidence of at least three building phases became clear. The latest phase survived only in the central section of the building. Its walls were made of rough stone with mud cement bonding and a pavement of red bricks and stone slabs. Almost exactly underneath these stone walls, earlier mudbrick walls were found. In spite of the incompleteness of the excavation, many questions concerning the ground-plan of this phase could be settled. The dimensions of the church were c. 15 by 10 m with the main axis oriented from southwest to northeast. The three western rooms had a pavement of reused red bricks. In the central part of the structure were the nave and aisles, of approximately similar width, separated by suspected pillars of red brick. Inside the apse, the lower part of the pulpit was preserved. The apse is flanked by two sacristies which are connected by a passage behind the apse. This feature clearly classifies the building as belonging to the type of the Classic Nubian Church (according to Adams 1965: type 3c). It is thus dated c. 800 to 1250 AD. A unique find was a cross-shaped ceramic baptismal font in the diakonikon, i.e. the southern sacristy. After its removal, a predecessor basin became visible underneath. The lower basin was made of red bricks covered with lime plaster; it certainly belongs to an earlier phase of the church. Further finds from the church include numerous pieces of painted plaster which belong to the original wall decoration of the building – unfortunately, the small size of the fragments does not allow a reconstruction of the decorative program. Some structures south of the church were interpreted as forming part of the residential area of the fortress. This is indicated by large storage vessels of unburnt mud and by coarse pottery. But only a small area could be excavated as yet. A massive construction of mudbrick and red brick may represent an earlier enclosure wall, later reused as road surface. A predecessor of the medieval fortress is made probable by the presence of some finds of presumably pre-Christian date, e.g. a fragment of an archers’ loose and a mace head.

Excavation team: Daniela Billig, Tim Karberg, Andrea Schlickmann, Ralf Miltenberger, Khidir Abdelkarim Ahmed, Fawzi Hassan Bakhiet

Plan of the church in fortress MOG048

Plan of the church in fortress MOG048

Floors in rooms A and B (west) of the church at MOG048

Floors in rooms A and B (west) of the church at MOG048

The apse and the southern sacristy with the baptismal font

The apse and the southern sacristy with the baptismal font

Baptismal font of the church at MOG048

Baptismal font of the church at MOG048

Fragments of painted plaster from the church at MOG048

Fragments of painted plaster from the church at MOG048

Structures south of the church in fortress MOG048

Structures south of the church in fortress MOG048

5. The fortification MOG047

A second fortification, MOG047, c. 5 km upstream of Ras al-Jazira, was briefly visited in order to determine its potential for detailed future investigation. In its architectural layout, MOG047 significantly deviates from the medieval fortresses of the region. It is roughly square, the length of its enclosure walls ranging from c. 55 to 65 m. It has small bastions in all four corners. A special feature is the execution of the enclosure walls: they are built without mortar, of stone slabs which are not laid horizontally but placed on end instead. The assumption that MOG047 is of Meroitic date was checked through a test trench, but could not yet be finally confirmed.

Excavation team: Tim Karberg, Ralf Miltenberger, Fawzi Hassan Bakhiet, Andrea Schlickmann

The fortress MOG047 in the satellite image (source: Google Earth)

The fortress MOG047 in the satellite image (source: Google Earth)

View along the western fortification wall of MO047 towards the Nile

View along the western fortification wall of MO047 towards the Nile

Detail of the eastern fortification wall of MOG047 showing the characteristic building technique of upright stone slabs

Detail of the eastern fortification wall of MOG047 showing the characteristic building technique of upright stone slabs

6. Geographical survey

In the geographical subproject, the island of Mograt was mapped in order to produce a cartographical basis for future archaeological investigations. In a wider context, the resulting map forms an important analytical instrument, e.g. for studies on the distribution of recent settlements and farmland. During the survey, which covered the entire island, a wide range of data on the physical and social geography of Mograt was gathered as well.

Geographical survey: Matthias Ritter

Graffiti at the Great Enclosure of Musawwarat es Sufra

1. The Great Enclosure and its graffiti

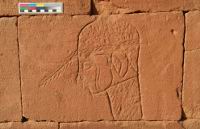

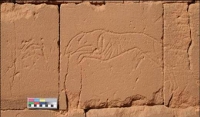

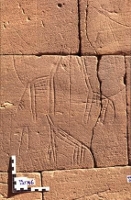

As a result of the ongoing political complications, it was impossible to undertake the projected 2008 rock art survey on Us island in the Fourth Cataract. Instead, the rock art recording team relocated at short notice to work on the extensive graffiti corpus of the Meroitic (c. 300 BC – 350 AD) Great Enclosure of Musawwarat es Sufra, c. 150 km north of Khartoum. The Great Enclosure is a unique but enigmatic complex of temples, other buildings, corridors, ramps and courtyards, which has stimulated the imaginations of many visitors. The function(s) of its various parts as well as the overall purpose of the site are contested. Recent hypotheses include interpretations as a pilgrimage centre, a royal hunting palace, the main sanctuary of the lion god Apedemak, etc. The official decorative programme is extremely limited – thus complicating insights into the function of the site. In contrast, the sandstone walls of the Great Enclosure carry the largest extant corpus of Meroitic (and later) incised inscriptional and pictorial graffiti. They include the southernmost Latin inscription so far known. Most of the other inscriptions are in Meroitic cursive script, among them numerous proskynemata appealing to the god Apedemak. The pictorial graffiti include a broad spectrum of motifs from the Meroitic world, e.g. depictions of human and/or superhuman figures, animals, objects, architectural features, or symbols. In the past, it was estimated that more than 2500 pictorial graffiti exist on the walls of the Great Enclosure of Musawwarat. The recent investigations permit us to raise this number considerably. However, they also show that the graffiti are threatened by rapid deterioration as well as by the rising number of visitors to the site, who deface them by adding their own signatures. The graffiti of the Great Enclosure of Musawwarat es Sufra have not undergone detailed discussion and publication so far. This is regrettable, as they entail a potential to gain information about the use of the Great Enclosure and the function of individual rooms and of the building complex as a whole. Moreoever, their study is of great significance for a better understanding of unofficial Meroitic art and ritual practice; this potential has hitherto remained untapped. Also, as close similarities exist in motif choice and stylistic traits between the Musawwarat graffiti and the rock art of the Fourth Cataract, the study of the more precisely dated graffiti can help us gain a better understanding of rock art in the wider region.

2. The 2008 documentation process

The graffiti of the Great Enclosure were first systematically studied in the late 1960s and again in the mid 1990s by researchers of Humboldt University Berlin; in their majority they remain unpublished, however. In order to finally bring the entire corpus to publication and to allow for the first time the exact description, situation and identification of each graffito, a selection of walls were: - photographed block by block under different lighting conditions to allow for maximum visibility of all lines present, - described block by block according to a range of criteria (state of preservation of block surface; form, patination, line characteristics, superimpositions, juxtapositions, etc.), - described room by room. To facilitate this work and systematize the recording, a thesaurus of motifs was developed. Various observations were noted concerning the clustering or regular spacing of motifs, the presence or absence of plaster on the walls, possible ‘traditions’, etc. Selected graffiti were traced directly from the walls onto transparent plastic sheets. Some were traced on two layers of plastic to allow the easy visualization of various phases of marking. Significantly more accurate drawings of some important motifs were thus created.

Head. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

Head. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

Dog chasing rabbit. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

Dog chasing rabbit. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

Horned altar. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

Horned altar. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

Bird and offering vessel. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

Bird and offering vessel. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

Giraffes. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

Giraffes. Graffito from the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat

3. First results of the documentation process

Recent fieldwork suggests that a great number of the graffiti of the Great Enclosure date to the Meroitic period and that they were thus made while the building complex was in use. This is suggested, among several other factors, by the re-use in younger building phases of blocks with existing pictorial graffiti, now turned upside-down. The large number of superimpositions between motifs and differences in patination open the possibility to work out a finer chronology of these graffiti. The great regularity of the incised lines and the centring of many graffiti in the middle of the blocks suggest that they were incised directly into the block surface and not through a layer of plaster as had been argued in the past. This implies that the walls in most parts of the Great Enclosure were not covered with a durable plaster and painted as had been assumed in an attempt to explain the scarcity of remains of an official decorative programme. Moreover, there is good indication that the placement of specific motifs was meaningful. Some motifs, such as ‘horned altars’, were found only at specific heights on selected walls.

Financial support:

Packard Humanities Institute

Project director:

Prof. Dr. Claudia Näser

Field team 2008:

Daniela Billig, M.A. (general field director, field director, medieval archaeology)

Reinhold Schulz, M.A. (field director: prehistory)

Dr. Cornelia Kleinitz (field director: rock art project)

Dr. Fawzi Hassan Bakhiet (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums)

Prof. Dr. Khidir Abdelkarim Ahmed (archaeology)

Peter Becker (architecture)

Petra Weschenfelder, M.A. (pottery analysis)

Alexandra Bergmann (archaeology)

Tim Karberg, M.A. (archaeology)

Andrea Schlickmann, M.A. (archaeology)

Ralf Miltenberger (archaeology)

Björn Briewig (archaeology)

Jens Weschenfelder (rock art research)

Mathias Ritter (physical geography)

Jürgen Dombrowski (technical support, photography)

Philipp Georges (technical support)