The second half of 2021 was dominated by news of Izabela, a pregnant woman who died in September in a hospital in Pszczyna, in the south of Poland. In October, the family lawyer has shared the news of her death on twitter, stating she was a victim of the anti-abortion legislation in Poland. Izabela was 22 weeks pregnant and presented with lack of amniotic fluid. She died of sepsis within 24 hours of being admitted. Izabela’s family believe doctors delayed removing the fetus from her womb, and waited with intervention in hope the fetus stops having a heartbeat first. Izabela herself was aware that the intervention might be delayed due to doctors’ fears connected to the abortion ban, as she wrote in text messages to her family (source).

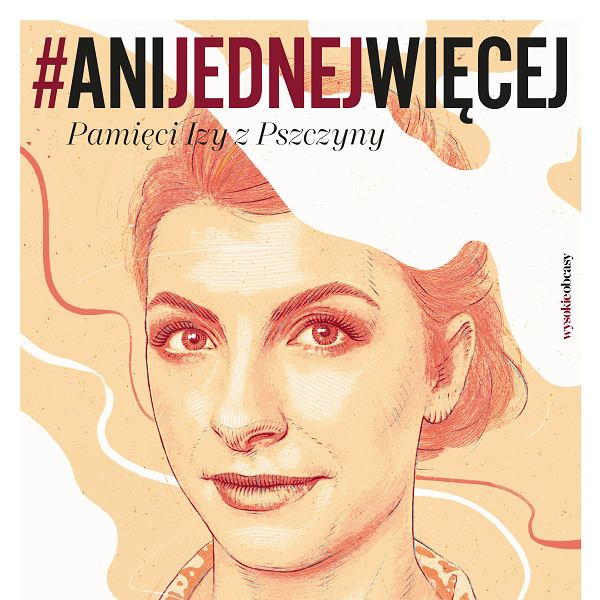

The first demonstrations prompted by Izabela’s death, were organized on the 1st of November, a national holiday of All Saints, which traditionally in Poland is a day of family celebrations. Later in November, a second wave of even more numerous demonstrations was organized in several Polish cities (source). What distinguished Izabela from other victims, and these demonstrations from all previous ones, is that Izabela’s family allowed activists to use her name and provided photos of her face, which were printed out and held up during protests. Her name and her face, made public, helped visualize the person behind the news story. Izabela was relatively young (30), had a husband and a nine-year-old daughter. (Another case, similar to Izabela’s was also reported later that year: the woman lived in Świdnica, her name was not made public).

Women taking part in the demonstrations lit candles, held Izabela’s photos, and placards with slogans: “Not one more” (Ani jednej więcej), “She also had a heartbeat” or “Her heart was also still beating” (Jej serce też ciągle biło), “We are sorry we couldn’t do anything” (Przepraszamy że nie mogłyśmy nic zrobić). The atmosphere held both anger and mourning.

The political responses to Izabela’s death were unsurprising. While Izabela’s family blamed the hospital and were convinced the doctors did not act in her best interest, but were rather motivated by fear of violating abortion laws (source), the authorities pivoted to remove the event from the context of abortion criminalization, and ordered an inspection in the hospital, in an effort to frame Izabela’s death as an isolated medical malpractice (source, source).

The European Parliament reacted to the news by issuing a resolution condemning the Polish governments treatment of abortion access (source, source). Additionally, the Dutch Parliament moved to finance abortion for women who cannot have them in Poland (source). These events are part of a long-going disagreement between the Polish governments and European Union authorities regarding the issue of abortion. The news has further contributed to a strain on this relationship.

As a researcher, I was reminded about the real cost of abortion criminalization. Researching abortion activism and its many innovations has allowed me to focus on hope and solidarity; it may have also contributed to focusing on a rather optimistic picture. In it, abortion is criminalized in Poland, but a savvy group of activists and organizations has all but solved the problem of abortion access by facilitating access to either abortion pills or abortion migration. Izabela’s death reminded me that there are still very real casualties of the abortion ban. As long as abortion is criminalized and stigmatized, gynecology and obstetrics are not whole. One medical procedure, removing the fetus from the womb when the chances of its survival are slim or none, is still so stigmatized, that the doctors avoid it, seemingly at all cost. It was too late for migration, I’m not sure pills could have help. Izabela died understanding that she is a victim of the abortion ban. Her death is so difficult to process, because it was avoidable. She did not die of a new, incurable disease. She died of sepsis, in a perfectly modern hospital, after a common pregnancy complication.

Can the development of abortion activism, based on solidarity and demedicalization, solve all problems stemming from criminalization? Can part of pregnancy care be removed from hospitals, while another part still relies on hospital care? Can medicine’s approach to pregnancy and women’s agency be reformed?