by the CrimScapes Research Team

This policy brief stems from our three-year research project called CrimScapes: Navigating Citizenship through European Landscapes of Criminalisation (2020–

2024).

Many strands of our research explored the social life of criminal law: its widespread,

unforeseen effects, not only individual stigmatisation, but also the ways it limits communities’ abilities to participate in democratic processes or seek social justice.

Hence, the conclusions from our research analyses have been condensed into an accessible, concise form for this policy brief.

We hope our insights from fieldwork and policy recommendations can bring clarity

and inspiration to further advance critical research, bring about a much-needed

change in the employed policies, and, ultimately, strengthen social justice.

Criminalisation represents an expanding form of governance, where an increasing

array of identities, behaviours, communities, and aspects of daily life fall under

the purview of criminal law, often at the expense of principles of social justice.

Social issues are increasingly viewed through the lens of criminalisation, framing them as threats rather than challenges to be addressed through social policies

such as public health initiatives, access to rights, or support-oriented or educational

interventions. For instance, the criminalisation of practices like HIV transmission or drug use shifts the focus from public health concerns to punitive measures.

This approach, which portrays social problems as imminent threats necessitating

enhanced efforts to protect an alleged vulnerable society, can fuel authoritarianism and populism while limiting personal freedoms. By creating dichotomies

of “good” versus “bad”, and attributing responsibility for structural issues to individuals or communities, criminalisation exacerbates societal tensions and marginalises already disenfranchised communities.

Moreover, the pervasive reach of criminal law into everyday life has worrying social

implications. Instances where individuals hesitate to seek necessary assistance

due to fear of legal repercussions, such as medical care for drug overdoses or protection and justice in the case of violence, illustrate the chilling effect of criminalisation. Similarly, criminalising survival strategies like migration or sex work further marginalises already vulnerabilised individuals and perpetuates inequalities.

Stigmatisation, social isolation, and barriers to organising or accessing essential services are among the detrimental effects of criminalisation. Despite its purported aim to protect the most vulnerable, criminalisation often increases their susceptibility to harm and perpetuates cycles of disadvantage. Furthermore, the wide-ranging and sometimes unforeseeable social consequences

of criminalisation, such as homelessness or increased poverty, highlight the complexities and drawbacks of this approach.

Recommendations:

- Tackle social issues through comprehensive social policies, including initiatives designed to enhance access to rights, healthcare, and education.

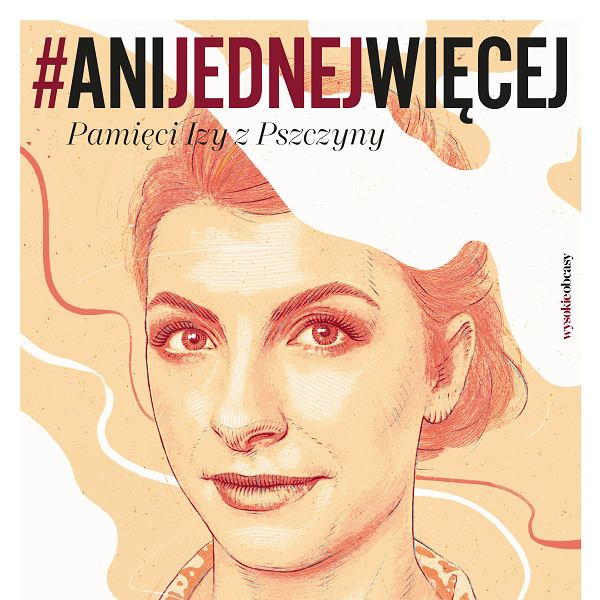

- Advocate for decriminalisation in areas such as abortion, HIV, sex work, drug use, and poverty-related crime, with practical examples demonstrating positive outcomes.

- Safeguard the right of criminalised and disenfranchised communities to self-organise and establish networks of support.

- Engage criminalised and disenfranchised communities in policy-making processes.

- Implement harm reduction strategies with proven effectiveness, illustrated by many successful case studies.

Read and download full version here: