Anyone who practices sex in public in Germany today must expect criminal consequences. Section 183a of the German Penal Code regulates the local circumstances in which sexual acts may take place. It criminalizes people who intentionally or willfully annoy other people by having sex in public, and threatens them with a fine or imprisonment of up to one year. The paragraph primarily targets and regulates two forms of consensual sex: sex work and cruising.

Sex in public, however, has not always been regulated and punished in the same way. The regulation of sex in public is subject to multifaceted changes and thus also points to changing notions of decency and morality. It raises the questions: How can sexuality be articulated in the public sphere? Who feels disturbed by whom and what? What is considered a public nuisance? Where should who be protected from sexualized or gender-based assaults?

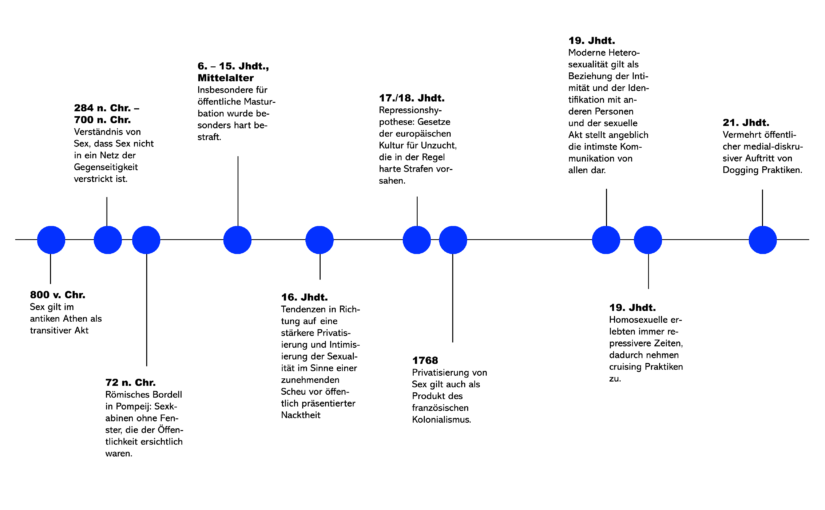

A brief look back into history shows that sexuality in public space was once negotiated along completely different lines. In ancient Athens in 800 B.C., sex was considered a transitive act, an action that was not reciprocal. In the excavation site of Pompeii, there are wall paintings that show evidence of permissive, sexual acts in bathhouses or brothels. It was not until the emergence of modern notions of intimacy and the bourgeois nuclear family that the structural separation of public and private spheres emerged. Sexuality and intimacy were assigned to the private, closed space and limited to it.

This separation is reflected today in §183a: certain public sexual practices are regulated and criminalized with reference to a mandate to protect. In the jurisprudence, reference is made to a so-called “objective third party” who is disturbed by the sexual practices. This “objective” or also “imagined third party” (Barnert 2018) functions as an argumentation figure, stands outside of the event and forms a bridge between abstract law and concrete life. In doing so, this figure of argumentation is supposed to help find a yardstick in the “flickering between facts and norm” (Kocher 2019: 408). Sociologists of law such as Eva Kocher (2019) have shown that the sense of shame and decency attributed to this figure is based on contemporary values and notions of citizenship, paternalism, and reason. By inscribing implicit bourgeois-modern notions of intimacy and sexuality, privacy and publicity into criminal law via the figure of the “objective third,” regulation operates beyond the mere framing of sexual practices (Berlant & Warner 1989: 553-557); it promotes the separation of private life from the public sphere of wage labor, politics, and public space.

Literature

Barnert, E. (2008): Der eingebildete Dritte: Eine Aurgumentationsfigur im Zivilrecht. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Bartz, D. (2002): Die Scham erobert den Ozean der Liebe. Mare, die Zeitschrift der Meere. https://www.mare.de/die-scham-erobert-den-ozean-der-liebe-content-2505.

Zuletzt abgerufen: 20.06.2021.

Berlant, L., & Warner, M. (1998): Sex in Public. Critical Inquiry, 24(2), 547-566.

Fagan, B. M. (1998): Clash of cultures. AltaMira Press, Lanham.

Halperin, D. M. (1989): Is There a History of Sexuality? History and Theory,

28(3), 257.

Fradella, H.F. & Sumner, J. M. (2016): Sex, Sexuality, Law, and

(In)justice. Routledge.

Roth, N. (2014): Freundschaft und Liebe. Codes der Intimität in der höfischen

Epik des Mittelalters. Frankfurt. https://d-nb.info/1149289295/34.

Zuletzt abgerufen: 20.06.2021.

Stumpp, B.E. (1998): Prostitution in der römischen Antike. Berlin

Vokery, C. (2010): Gassigehen mit Glücksgefühl. Spiegel Panorama Online. https://www.spiegel.de/panorama/gesellschaft/freiluft-sex-in-england-gassigehen-mit-gluecksgefuehl-a-723214.html.

Zuletzt abgerufen: 20.06.2021.

Text and timeline were created in the context of the MA seminar “Crime, Criminalization, and Gender” at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (summer semester 2021). We would like to thank Sabrina Bahlo, Tülin Fidan, Melina Madoures, Sabrina Mainz, JJ Maurer and Muriel Weinmann for their permission to publish the timeline on our blog. The group work was summarized by Carmen Grimm.