by Jérémy Geeraert

This is a living timeline of major events, laws and practices marking the criminalisation of search and rescue activities in solidarity with migrants in distress.

by Jérémy Geeraert

This is a living timeline of major events, laws and practices marking the criminalisation of search and rescue activities in solidarity with migrants in distress.

By Agata Dziuban

This is a living timeline of the criminalisation of sex work in Poland.

by Friederike Faust

Why do women commit crime, and how should they be punished? This CrimLine reconstructs in excerpts how the social image of criminal women, corresponding criminological explanations as well as penal policies have changed in Germany.

Delinquency and norm violations by women have always been in particular need of explanation, as they diverge with conceptions of the female nature and role. Linked to the question of the causes and motives of female criminality is the question of the appropriate and effective punishment of women.

This CrimLine is intended to help understand how today’s women’s penal system is organized legally and politically. The CrimLine reveals the social morals and imaginaries about female crime that come to shape the contemporary treatment of incarcerated women. Spectacular criminal cases will be used to illustrate how women’s crimes are dealt with differently over the years and in accordance with changing social gender relations. These social debates also reflect the paradigm shifts in the criminological theorization of female delinquency. At the same time, criminology as an applied science influences national and international penal politics and legislation, and thus has sever impact on the everyday experiences of sentenced and imprisoned women.

Anyone who practices sex in public in Germany today must expect criminal consequences. Section 183a of the German Penal Code regulates the local circumstances in which sexual acts may take place. It criminalizes people who intentionally or willfully annoy other people by having sex in public, and threatens them with a fine or imprisonment of up to one year. The paragraph primarily targets and regulates two forms of consensual sex: sex work and cruising.

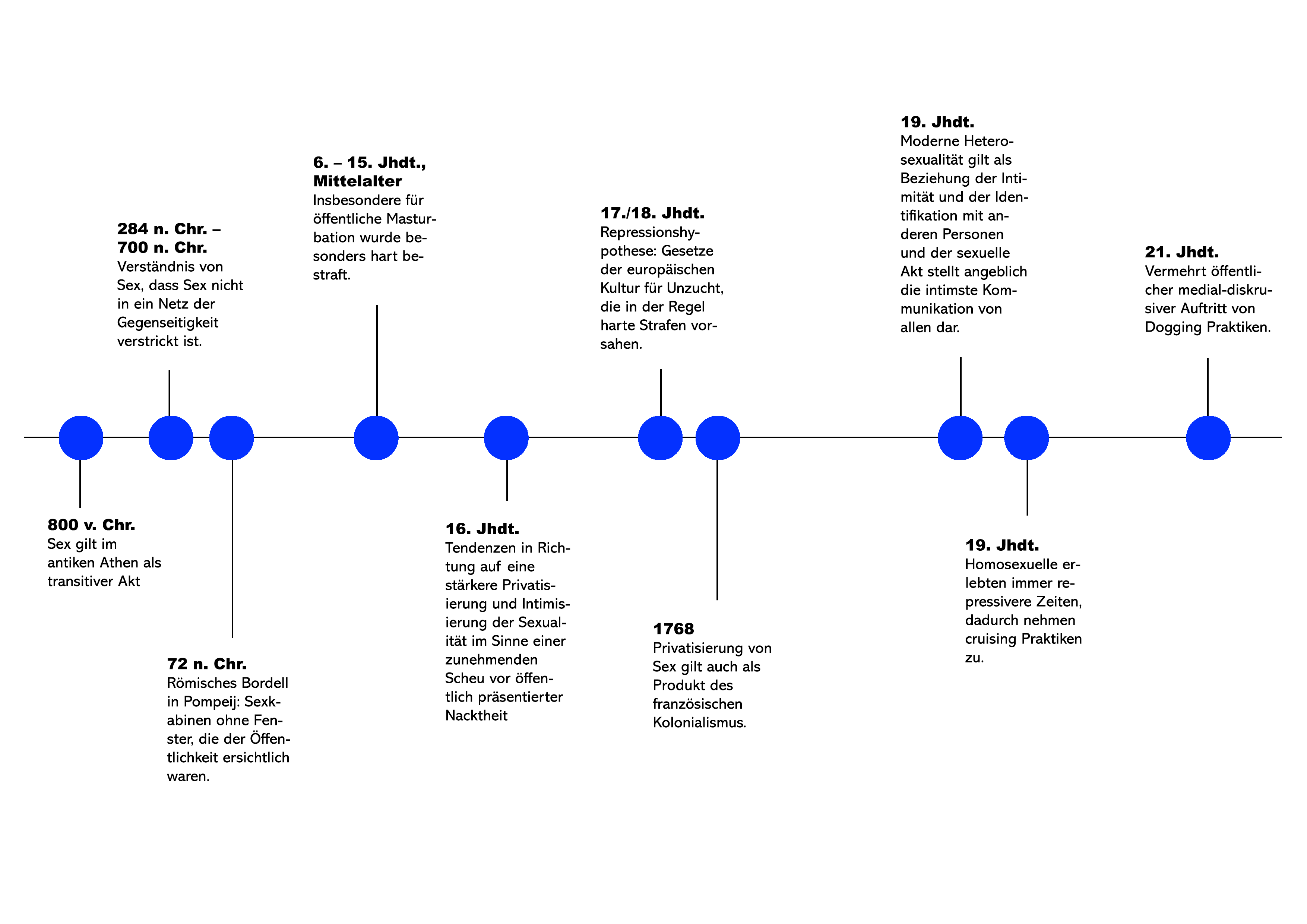

Sex in public, however, has not always been regulated and punished in the same way. The regulation of sex in public is subject to multifaceted changes and thus also points to changing notions of decency and morality. It raises the questions: How can sexuality be articulated in the public sphere? Who feels disturbed by whom and what? What is considered a public nuisance? Where should who be protected from sexualized or gender-based assaults?

A brief look back into history shows that sexuality in public space was once negotiated along completely different lines. In ancient Athens in 800 B.C., sex was considered a transitive act, an action that was not reciprocal. In the excavation site of Pompeii, there are wall paintings that show evidence of permissive, sexual acts in bathhouses or brothels. It was not until the emergence of modern notions of intimacy and the bourgeois nuclear family that the structural separation of public and private spheres emerged. Sexuality and intimacy were assigned to the private, closed space and limited to it.

This separation is reflected today in §183a: certain public sexual practices are regulated and criminalized with reference to a mandate to protect. In the jurisprudence, reference is made to a so-called “objective third party” who is disturbed by the sexual practices. This “objective” or also “imagined third party” (Barnert 2018) functions as an argumentation figure, stands outside of the event and forms a bridge between abstract law and concrete life. In doing so, this figure of argumentation is supposed to help find a yardstick in the “flickering between facts and norm” (Kocher 2019: 408). Sociologists of law such as Eva Kocher (2019) have shown that the sense of shame and decency attributed to this figure is based on contemporary values and notions of citizenship, paternalism, and reason. By inscribing implicit bourgeois-modern notions of intimacy and sexuality, privacy and publicity into criminal law via the figure of the “objective third,” regulation operates beyond the mere framing of sexual practices (Berlant & Warner 1989: 553-557); it promotes the separation of private life from the public sphere of wage labor, politics, and public space.

Literature

Barnert, E. (2008): Der eingebildete Dritte: Eine Aurgumentationsfigur im Zivilrecht. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Bartz, D. (2002): Die Scham erobert den Ozean der Liebe. Mare, die Zeitschrift der Meere. https://www.mare.de/die-scham-erobert-den-ozean-der-liebe-content-2505.

Zuletzt abgerufen: 20.06.2021.

Berlant, L., & Warner, M. (1998): Sex in Public. Critical Inquiry, 24(2), 547-566.

Fagan, B. M. (1998): Clash of cultures. AltaMira Press, Lanham.

Halperin, D. M. (1989): Is There a History of Sexuality? History and Theory,

28(3), 257.

Fradella, H.F. & Sumner, J. M. (2016): Sex, Sexuality, Law, and

(In)justice. Routledge.

Roth, N. (2014): Freundschaft und Liebe. Codes der Intimität in der höfischen

Epik des Mittelalters. Frankfurt. https://d-nb.info/1149289295/34.

Zuletzt abgerufen: 20.06.2021.

Stumpp, B.E. (1998): Prostitution in der römischen Antike. Berlin

Vokery, C. (2010): Gassigehen mit Glücksgefühl. Spiegel Panorama Online. https://www.spiegel.de/panorama/gesellschaft/freiluft-sex-in-england-gassigehen-mit-gluecksgefuehl-a-723214.html.

Zuletzt abgerufen: 20.06.2021.

Text and timeline were created in the context of the MA seminar “Crime, Criminalization, and Gender” at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (summer semester 2021). We would like to thank Sabrina Bahlo, Tülin Fidan, Melina Madoures, Sabrina Mainz, JJ Maurer and Muriel Weinmann for their permission to publish the timeline on our blog. The group work was summarized by Carmen Grimm.

Wer in Deutschland heute Sex in der Öffentlichkeit hat, muss mit strafrechtlichen Konsequenzen rechnen. Der §183a des Strafgesetzbuches reguliert die örtliche Gegebenheit, an der sexuelle Handlungen stattfinden dürfen. Er kriminalisiert Personen, die mit Sex in der Öffentlichkeit andere Personen absichtlich oder willentlich verärgern, und droht mit einer Geldstrafe oder einer Freiheitsstrafe von bis zu einem Jahr. Der Paragraph trifft und reguliert vor allem zwei Formen einvernehmlichen Sexes: Sexarbeit und Cruising.

Sex in der Öffentlichkeit wurde jedoch nicht schon immer auf gleiche Art und Weise reguliert und geahndet. Die Regulierung von Sex in der Öffentlichkeit unterliegt vielseitigen Veränderungen und verweist damit auch auf sich wandelnde Vorstellungen von Anstand und Sitte. Sie wirft die Fragen auf: Wie kann Sexualität im öffentlichen Raum artikuliert werden? Wer fühlt sich durch wen und was gestört? Was gilt als öffentliches Ärgernis? Wo soll wer vor sexualisierten oder genderbasierten Übergriffen geschützt werden?

Dass Sexualität im öffentlichen Raum auch mal entlang ganz anderer Fragen und Vorstellungen verhandelt wurde, zeigt ein ausschnittartiger Blick zurück in die Geschichte. Im antiken Athen galt 800 vor Christi Sex als transitiver Akt, als eine Handlung, die nicht auf Gegenseitigkeit beruht. In der Ausgrabungsstätte von Pompeij finden sich Wandmalereien, die Hinweise auf freizügige, sexuelle Akte in Badehäusern oder Bordellen zeigen. Erst mit dem Aufkommen moderner Intimitätsvorstellungen und der bürgerlichen Kleinfamilie entstand die strukturelle Trennung von Öffentlichkeit und Privatheit. Sexualität und Intimität wurden dem privaten, geschlossenen Raum zugeordnet und auf diesen begrenzt.

Diese Trennung spiegelt sich heute im §183a: Bestimmte öffentliche Sexualpraktiken werden unter Verweis auf einen Schutzauftrag reguliert und kriminalisiert. In der Rechtsprechung wird dabei auf einen sogenannten „objektiven Dritten“ verwiesen, der von den Sexualpraktiken gestörten wird. Diese*r „objektive“ oder auch „eingebildete Dritte“ (Barnert 2018) fungiert als Argumentationsfigur, steht außerhalb des Geschehens und bildet eine Brücke zwischen abstraktem Recht und konkretem Leben. Dabei soll diese Argumentationsfigur helfen, einen Maßstab im „Flimmern zwischen Sachverhalt und Norm“ (Kocher 2019: 408) zu finden. Rechtssoziolog*innen wie Eva Kocher (2019) haben gezeigt, dass das dieser Figur zugeschriebene Scham- und Anstandsgefühl auf gegenwärtigen Werten und Vorstellungen von Bürgerlichkeit, Paternalismus und Vernunft beruht. Indem sich über die Figur des „objektiven Dritten“ implizite bürgerlich-moderne Vorstellungen von Intimität und Sexualität, Privatheit und Öffentlichkeit in das Strafrecht einschreiben, wirkt die Regulierung über die bloße Ausgestaltung der Sexualpraktiken hinaus (Berlant & Warner 1989: 553-557); sie befördert die Trennung des privaten, familiären Lebens von der öffentlichen Sphäre der Lohnarbeit, der Politik und des öffentlichen Raums.

Zitiervorschlag: Genealogie von Sex in der Öffentlichkeit, JJ Maurer, lizenziert unter einer CC BY-SA 4.0, Creative Commons Namensnennung – Nicht-kommerziell – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International Lizenz.

Literatur

Barnert, E. (2008): Der eingebildete Dritte: Eine Aurgumentationsfigur im Zivilrecht. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Bartz, D. (2002): Die Scham erobert den Ozean der Liebe. Mare, die Zeitschrift der Meere. https://www.mare.de/die-scham-erobert-den-ozean-der-liebe-content-2505. Zuletzt abgerufen: 20.06.2021.

Berlant, L., & Warner, M. (1998): Sex in Public. Critical Inquiry, 24(2), 547-566.

Fagan, B. M. (1998): Clash of cultures. AltaMira Press, Lanham.

Halperin, D. M. (1989): Is There a History of Sexuality? History and Theory, 28(3), 257.

Fradella, H.F. & Sumner, J. M. (2016): Sex, Sexuality, Law, and (In)justice. Routledge.

Roth, N. (2014): Freundschaft und Liebe. Codes der Intimität in der höfischen Epik des Mittelalters. Frankfurt. https://d-nb.info/1149289295/34. Zuletzt abgerufen: 20.06.2021.

Stumpp, B.E. (1998): Prostitution in der römischen Antike. Berlin

Vokery, C. (2010): Gassigehen mit Glücksgefühl. Spiegel Panorama Online. https://www.spiegel.de/panorama/gesellschaft/freiluft-sex-in-england-gassigehen-mit-gluecksgefuehl-a-723214.html. Zuletzt abgerufen: 20.06.2021.

Text und Timeline entstanden im Rahmen des MA-Seminars „Kriminalität, Kriminalisierung und Geschlecht“ an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (Sommersemester 2021). Wir danken Sabrina Bahlo, Tülin Fidan, Melina Madoures, Sabrina Mainz, JJ Maurer und Muriel Weinmann für ihre Erlaubnis, die Timeline auf unserem Blog zu veröffentlichen. Die Gruppenarbeit wurde zusammengefasst von Carmen Grimm.