Luca

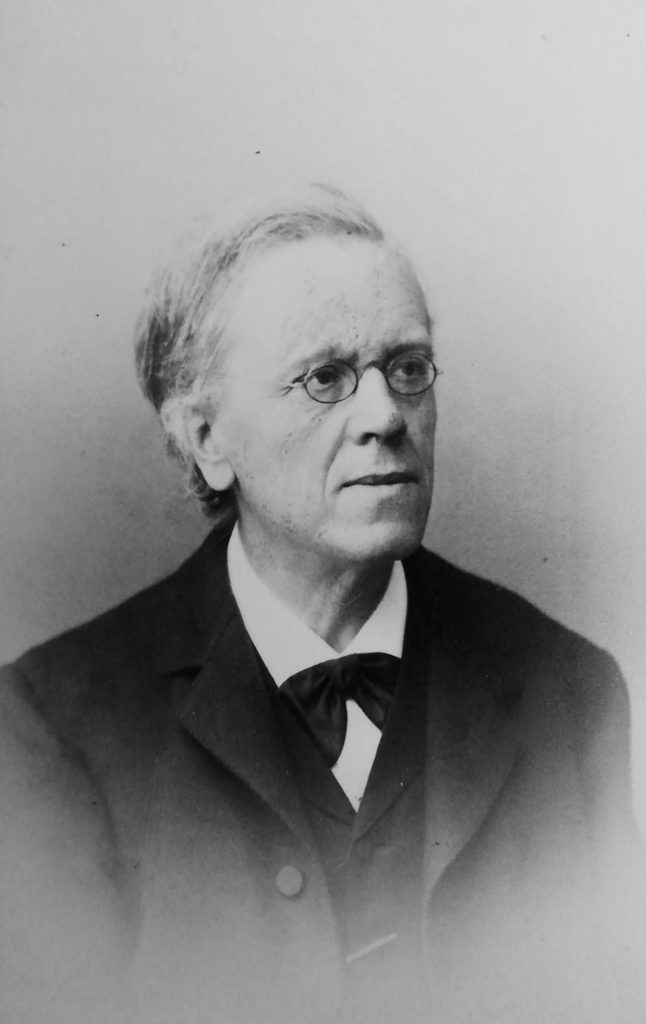

is a research assistant and PhD candidate at the University of Erfurt’s Max Weber Centre for Advanced Cultural and Social Studies as well as at the University of Graz. Born in Friuli, he studied philosophy in Turin and Milan, specialising in the thought of Erik Peterson. Dealing in particular with the philosophy of religion and the contemporary history of Christianity, he is currently working on Franz C. Overbeck.

Thomas

is one of the founding members of the Simone Weil denʞkollektiv.

The French political theorist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865), the German theologian Franz C. Overbeck (1837-1905), and the French philosopher Simone Weil (1909-1943) share an interest in rethinking socialism against the backdrop of a sharp criticism of Christianity. Proudhon lays the foundation of this philosophy, leaving Overbeck and Weil to carry on his heritage, albeit in opposed directions. All three figures mark an often ignored but essential juncture between the 1840s and the 1940s in the history of ideas concerning the relationship between socialism and Christianity.

In what follows, we introduce our three thinkers and areas of their overlapping interest, all through catalogical notes to map a very short history of ideas often overlooked in academia.

Proudhon, Weil, and Overbeck at a Glance

o Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was a political thinker often associated with the concept of anarchy. He dealt, in particular, with two problems bequeathed by the Enlightenment: social inequality and the failed development of the individual. When combined, these two problems reveal an even greater one to which Proudhon almost linked his name: property. According to him, property ratifies the supremacy of the victors in the struggle for power. Herein lies Simone Weil’s interest in Proudhon: both theorize that property and sovereignty are legitimised by history and transcendence, or, to put it differently, that the law of force and power in the double articulation of war and religion are the cornerstone of the political community.

o In Proudhon’s eyes, the post-war process of institutionalisation shows that the political community uses power to legitimise the relations established during war; the winners change the name to the law of force by improperly matching it with the law of nature. Property is nothing but the final result of this corrupt process.

Yet, Proudhon does not want to abolish property, as property is the expression of individual autonomy. And as Franz C. Overbeck [1] observes, Proudhon assigns property a crucial role and regards it as one of the hallmarks of social progress. Despite this, he aims for a social equilibrium between the individual, social justice, and reason – the outcome of which is the so-called “libertarian socialism”.

Reason must manifest itself as a collective reason, namely as the embodiment of a system of relations to be pursued through public debate. Thus Proudhon does not advocate revolution itself, but rather a social science able to engender a critical attitude.

Franz C. Overbeck on Proudhon

Despite the size of the Overbeckian bequest in the “Franz C. Overbeck” archive at the University of Basel, the following reconstruction of Overbeck’s reading of Proudhon is based exclusively on other published material, primarily from the Kirchenlexicon. Since Overbeck took unrelated “notes” throughout various periods of his life –often while working on entirely diverse topics– without ever organizing them, I attempted some semblance of order by resorting to a list format, as follows.

o Overbeck knows Proudhon through reading Of Justice in the Revolution and the Church (De la justice dans la révolution et dans l’Église, 1858) and Jesus and the Origins of Christianity (Jésus et les origines du christianisme, posthumous), and É. Faguet’s Politicians and Moralists of the 19th Century (Politiques et moralistes du XIXe siècle, 1891).

o Of the first of these texts, he reproduces in his Kirchenlexicon two extracts:

“Without being afraid of the accusation of atheism, I cannot, however, allow it to degenerate into defamation and ostracism. Ever since my birth, I have been thinking about God, and I recognise no one more than myself the right to talk about him”.[2]

“Religion is the mystical lover of the Spirit, the companion of its young and free loves. Similar to Homer’s warriors, the Spirit does not dwell alone in its tent: this Cupid must have a lover, a Psyché. Jesus, who forgave the Magdalene, taught us to be lenient towards the wooers. But the day comes when the Spirit, tired of its own vitality, thinks of joining, through an indissoluble marriage, Science, the severe matron, that the Gnostics, those socialists of the second century, called Sophia, wisdom. There, for a few moments, the Spirit seems to be divided in itself; there are ineffable reminiscences and tender reproaches. More than once, the two lovers thought they had been reconciled: ‘I will be a Sophia for you’, says Religion; ‘I will also become wise, as you are, and always be more and more beautiful’. Vain hope! Inexorable fate! The nature of ideas, no more than that of things, cannot be modified in this way. Like the nymph abandoned by Narcissus, who from languishing ends up fading away in the thin air, Religion gradually turns into an impalpable phantom: it is only a sound, a remembrance, which rests in the deepest of the Spirit, and never entirely leaves the heart of man”.[3]

o Overbeck particularly appreciates Proudhon for his critique of religion, which, in his opinion, is in many ways similar to Nietzsche’s. He sees Proudhon and Nietzsche as emblematic and passionate representatives of individualism in contemporary culture. From Overbeck’s standpoint, as long as individualists want to place themselves at the centre of their own thoughts and actions in a coherent way, they will have to be able to dispense with the supernatural support of, and continuous recourse to, God. This is what, according to Overbeck, Proudhon achieves in his book Of Justice in the Revolution and the Church: emancipating morality from religion. He cuts the umbilical cord between man and God, who, until then, has always been considered indispensable by human beings. In this respect, Proudhon defines religion as expensive and superfluous to the state that human culture has reached.

o Overbeck does not characterise Nietzsche’s individualism as irreligious, although Overbeck does say that individualism and atheism go hand in hand. He deems Proudhon as the most dedicated connoisseur of atheism in the world and continually sets him next to Nietzsche. However, he notices a difference between the two, which he illustrates through parallelism with J.-J. Rousseau: just as Proudhon could not stand Rousseau’s idealism and attitude of posing as an artist, Overbeck cannot tolerate the same features in Nietzsche.

o Besides being a passionate individualist and fervent moralist, Overbeck’s Proudhon is fiercely anti-idealist, considering idealism the instrument of all seductions and the source of all the mystifications and abominations on earth. Building on these assumptions, Proudhon criticises Rousseau’s and E. Renan’s depictions of Jesus, in whom he sees a saviour. Overbeck alludes to Renan, portrayed as an idealiser of anarchism, to better outline Proudhon’s profile. Whereas Renan came to socialism from Christianity, Proudhon walks the opposite path, coming to Christianity by way of socialism.

o Concerning the relationships between socialism and Christianity (possible connections which Overbeck finds highly problematic), I quote a metaphor Overbeck adopts to describe them:

“In the dispute of our modern society and socialism on Christianity, there will be as much left of it [Christianity], as of the bone that two wild beasts bite around. Both of them want to incorporate it so that it will be consumed: this is the only sure result of the biting. Therefore, who presumes to label one of the two fighting beasts as the “defender” of the bone [of Christianity] can only make himself ridiculous”.[4]

o Although Overbeck makes no particular reference to Proudhon when comparing socialism with anarchism, it is useful to add that the German theologian prefers anarchism over socialism. Compared to the latter, anarchism appears more coherent, as long as it is concerned only with the individual and not, I say, idealistically, with society (which Proudhon sees as the outcome of the connection of individuals). Additionally, anarchism is more honest than socialism, if only through its indifference to the social democrats’ main principle of human equality, a principle in which Overbeck does not believe. In addition to equality, he depicts anarchism as indifferent to justice – and I assume that Overbeck was more sensitive to this point.

o Despite preferring anarchism to socialism, Overbeck is in no way an anarchist: he harshly attacks anarchism, claiming that in the name of freedom it destroys society without knowing that it will replace it with something very similar.

Simone Weil’s reception of Proudhon

o Simone Weil’s political thought is marked by her early love for the revolutionary syndicalism, her alienation from it, starting in 1934, and its lasting impact until her death. Long after its golden age from 1900 to 1910, revolutionary syndicalism hardly had any political influence when the young student Simone Weil first countered the movement. This situation of political ruin allowed Weil to dismantle the previous unity of political and ethical traditions within the movement and to develop a critical position towards Marxism. In the light of the ethical tradition (anti-authoritarian individualism and proletarian community), Simone Weil criticises the political tradition (the question of revolution and the role of unions within society). Her separation between ethics and politics reflects Weil’s distinction between a “source of inspiration” and a “doctrine” in her unfinished essay Sur les contradictions du marxisme in 1937. Here, she writes:

“I don’t believe that the labour movement will become alive again in our country as long as it doesn’t seek, I’m not saying doctrines, but a source of inspiration against what Marx and the Marxists combated and foolishly disdained: in Proudhon, in the unions of 1948, in the syndicalist tradition, in the anarchist spirit. Concerning a doctrine, the future alone, in the best of all cases, could perhaps provide an inspiration; not the past.”[5]

o It is Proudhon’s passion for the autonomy of the individual, the rethinking of property, and a proletarian particularism that inspires Weil when reading his texts. For her, Proudhon personifies an ethics which she sees as the initial inspiration for the labour movement of the previous century. As with Proudhon, Simone Weil does not want to abolish property as it constitutes individual autonomy.

o It is important to consider that Weil understands the term ‘ethics’ not as a simple reflection of moral behaviour but rather, in the sense of Charles Péguy’s Notre Jeunesse, as ‘mystique’; as the experience of an elementary internal intuition towards a society of free individuals characterised by dignity. [6]

o In Proudhon’s spirit, Weil envisions the future as the self-determination of the working class and as a form of anti-intellectualism in resistance to the authority of intellectuals over the laboring class. Weil demands an autonomous and independent culture of the working class and outlines in her 1943 L’Enracinement the founding of small co-operative self-determined workplaces in which neither foreman nor boss exist.

Proudhon’s thoughts on anti-authoritarian individualism and a proletarian community, which in terms of Weil is to be understood as ‘mystical ethics’ in Péguy’s sense, stands as canvas against which Simone Weil’s confrontation with Christianity takes shape. Weil’s fierce criticism of the Church as a collective within the political tradition and and her own deviant marginal traditions of individual mystical testimonies can be read in the context of this mystical-ethical framework of Proudhon’s critique of Christianity. Following in the footsteps of Proudhon, Weil also walks to Christianity via socialism, sharing his critique of all forms of religious authority over individuals.

o In Marseille, Weil rediscovers similar ideas in the JOC, Jeunesse ouvrière chrétienne, a group seeking to improve the welfare of the working-class youth independent of politics and even unconstrained by religion and the collective rage often entwined with both constructs. Weil’s experience with the JOC led her to reflect on the foundation of an alternative structure similar to religious orders but characterised by source d’inspiration of the anti-authoritarian individualism and the proletarian community, one could say, in the spirit of Proudhon.

New contributions:

Rachel Pafe (Berlin): The Miracle of Love Amidst the Crushes of War: Thinking through The Iliad with Susan Taubes and Simone Weil

Rachel Pafe is a writer and researcher interested in modern Jewish thought and critical theories of mourning. She is currently doing a joint PhD at Goethe University of Frankfurt and Université Lille. For more information visit Rachel’s Page. To read the German-version of the article, please click here. In her 1956 dissertation on French philosopher-mystic Simone

Marcus Steinweg (Berlin): “Notizen zu Simone Weil”

Leseschlüssel Die hier gelisteten – teils veröffentlichten, teils unveröffentlichten – Notizen von Marcus Steinweg beziehen sich allesamt auf Simone Weil. Die Liste ist offen und wird schrittweise durch neue Notizen erweitert. RIGORISMUS An Simone Weil besticht ihr Rigorismus und ihre Klarheit. Noch wenn sie sich dem Alltäglichen zuwendet, geht der Vektor ins Nichts. Nie versenkt

Elisabeth Hubmann (Genève): Organ improvisations in response to Simone Weil’s “Les Lutins du feu” (ca. 1921/22)

Il dansait, il dansait toujours, le peuple des âmes candides, des âmes des enfants qui ne sont pas encore nés; attendant leur tour d’être des hommes, les lutins se poursuivaient sur les bûches crépitantes. Simone Weil, Les Lutins du feu, 1921/22. ELISABETH HUBMANN Abstract Elisabeth is an organist, musicologist, and environmentalist active in Genève, Amsterdam