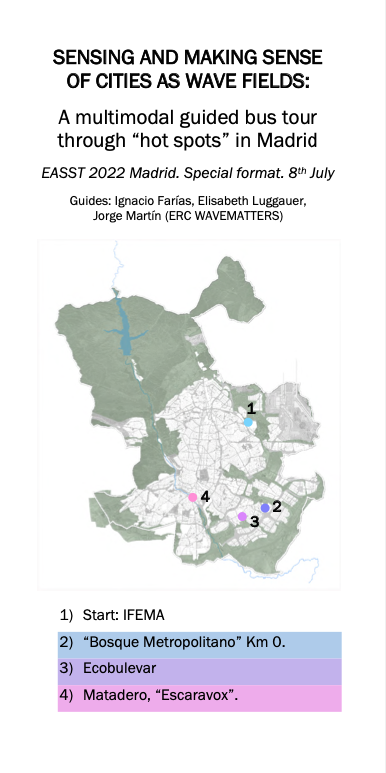

On the 8th of July 2022, more than 50 STS scholars attending the EASST conference in Madrid participated in a three-hour “thermodynamic” bus ride organised by the WAVEMATTERS team to selected “hot-spots” and heat infrastructures in Madrid. In our experimental journey, we visited three thought-provoking sites – the Bosque Metropolitano, the Eco-Bulevar, and the Escaravox – that stand for different types of urban heat infrastructures. At these places, we sensed heat with our bodies in perceptual walks, while in smaller groups, we reflected on our heat experiences, sensations, and strategies. And finally, aiming to make sense of heat, of bodily exposure to heat, and of cooling infrastructures, we gathered under some trees in a park next to Matadero, our last stop, for a closing round of discussion and reflection. In groups, we reflected on the visited sites with two questions in mind: What kind of practices and users do these sites invite or exclude? How do these sites infrastructure futures and which futures are those? We learned how each of the three sites is embedded in local urban textures, reflected upon the gaps between the visions and aims of planners and designers and the actual modes of appropriation, as well as on how heat is imagined in each of these sites, and on which heat futures, or future heat practices, are enacted in each of these interventions.

Sensing Heat at Bosque Metropolitano

When the bus rolled out of the conference venue, we had asked the participants to direct their attention to their bodies as instruments for sensing heat, but also as the means through which one is exposed to heat. During sensory walks at the three “hot spots”, we invited everyone to sense heat as thermic energy and as wave with the following questions: How does heat make you feel your body? What kind of body is that? What does your body urge you to do? What is it actually that you are sensing? We had also asked participants to bring any device they could think of to help against their bodily exposure to heat.

Our first stop was the “KM 0” of the Bosque Metropolitano project. Initiated in 2019, this project aims to introduce a 75km long forest, converting more than 35.000 ha of land into a “green” area. The aim is to interconnect existing parks and green areas around Madrid to create a forest belt around the city, enhancing biodiversity in urban areas, and cooling down the heavy urban heat island of Madrid. It will involve planting more than 1 million trees and millions of bushes, all carefully chosen among a selection of native species adapted to the climate and with low water requirements.

At KM 0, we invited participants to feel their body under the sun, to embody the experience of heat, and to engage the devices they brought to mediate such an experience. Sun radiation fell on our bodies. Our skin became hot and started to feel tense and dry. We felt that the heat went through the skin, and further into the body. The heat crawled into and under the clothes that covered our skin, and that should also protect the bodies from direct sun radiation. Some people found refuge under a few trees. Others found a water tap and used it to fill their spray bottles. We felt enveloped by a hot and sticky atmosphere. Breathing in and out, we soaked the hot atmosphere into our bodies. We felt slow, unable to move fast, breathing felt slower, and our bodies were sweating. Exposure was felt as the combined effect of sun radiation, thick air, reflecting surfaces, shadow infrastructures, bodily practices, and watering and cooling devices.

We strolled under the sun for about 15 minutes and then we all got back into our air-conditioned bus. The shock of cold air on our skin was a relief.

Reflecting on our experiences of the site, one thread concerned the very concept of an urban forest. Indeed, although called a “forest”, the place we visited reminded more of an urban park arranged of alleys framed by trees. But, what is a forest? Is it a type of place? A relational space? Or is it a kind of practice—e.g., a type of maintenance? The project of a metropolitan forest already carries its contradictions in the name: can a forest be urbanised and still be a forest? How can an urban (or urbanised) forest be designed and how could it become a multispecies meshwork of different trees, animals and human planners and visitors? Will the agency of tree species and their entangling with other non-human beings turn that place into the beginning of a surrounding green belt or into a desert-like stripe? Who and/or what will inhabit, use, and maintain that place in 10, 20 or 30 years? Will it be densely growing trees, joggers, cyclists, walking families and their pets, and animals oscillating between urban animals and wildlife, such as deer, boar, and birds?

Another thread of discussion involved the overarching urban development strategy of the city. The implementation of the Bosque Metropolitano will go along with other developments that will do the opposite—i.e. urbanizing land and “growing” buildings. In this context, we questioned how the land for this urban forest will be secured, planned, authorized, organized, purchased, and exchanged. And at what price? What will be its value or, rather, its cost? How will that correlate with the value of a tree? And, hence, what is the value of a tree? Are trees infrastructures that deliver ecosystems services? Are trees the means and mediators of biodiversity protection? Is the Metropolitan Forest a truly ecological project aiming to alleviate the city and ameliorate its urban space or is it just another political promise that will fade out after the four years of the current municipal government?

Making Sense of Cooling Devices at Eco-Bulevar

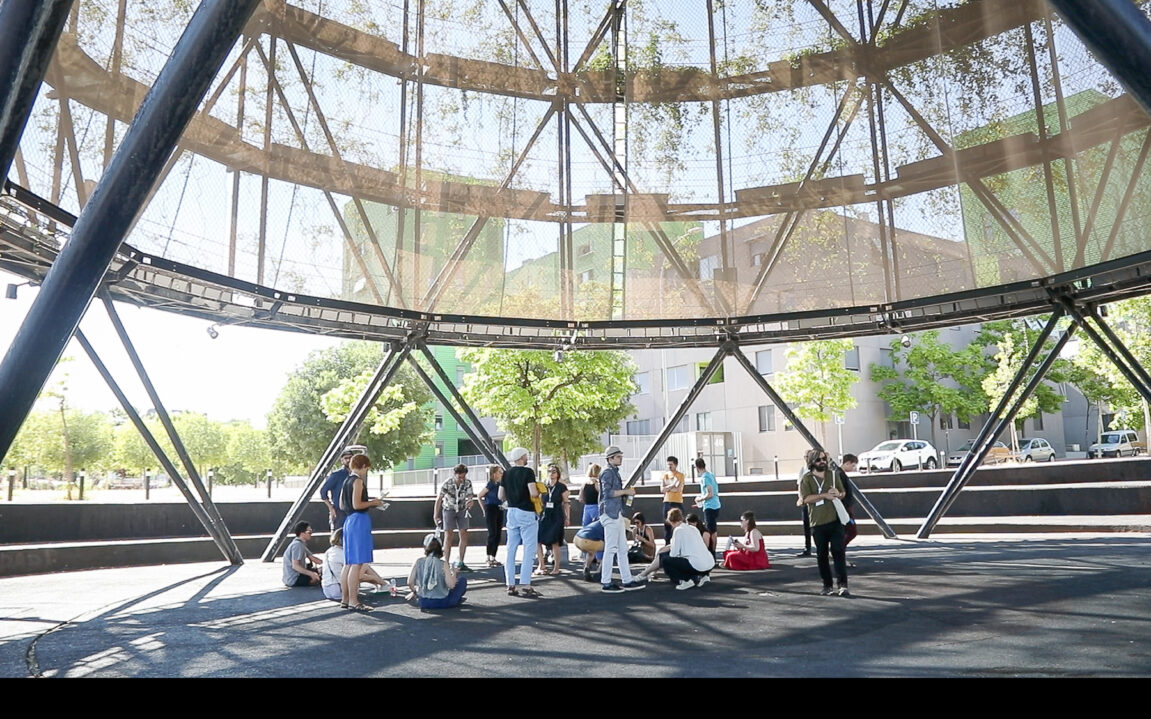

In our second stop, the Eco-Bulevar, we visited the “Air-Trees” designed by Ecosistema Urbano in 2004 after winning the “Bioclimatic Conditioning of C91 street” competition. The Eco-Bulevar was built between 2005 and 2008, just before the financial crisis, and is located in a social housing area in a middle-class neighborhood in the Villa de Vallecas’ district. Designed with social and environmental objectives in mind, the Eco-Bulevar aimed to “generate social activity” and adapt an outdoor space with a “bioclimatic system of passive air conditioning based on chilling by evapotranspiration”, as the architects describe (Ecosistema Urbano, 2007 and Interview with Diego García Setién, 2022). Like the Bosque Metropolitano, the Eco-Bulevar could be understood as a green infrastructure based on a “nature-based solution” that aims to cool down urban spaces. Yet, in contrast to the Bosque Metropolitano, the Eco-Bulevar’s Air-Trees did not include any actual trees. Its effect unfolded more in the atmospheric conditions it produced, which were mediated or translated by technological artefacts. This boulevard of three Air-Trees conditions the air through evapotranspiration and hence is intended as a nature-based idea to condition public air by lowering the temperature under and around the trees for up to 10 degrees Celsius. Another difference is that while the Bosque Metropolitano is imagined to ameliorate climatic conditions in Madrid as a whole, the Eco-Bulevar is a local solution. Indeed, built before the economic crisis of 2008, it was imagined to be the first of many similar atmospheric structures to be implemented in other public spaces of the city. These other atmospheric structures, however, have not been implemented.

Reflecting on their experiences at the site, the group remembered noticing a lot of movement and things going on under the first air-tree where the playground is positioned, which had also animated us to jump and climb on it. In contrast to that, the other two air-trees and the spaces in between the three trees were empty. The designers of the Eco-Bulevar originally intended to keep all three air-trees open and undefined, to invite and enable a broad variety of practices in and with the air-trees. However, the air-tree we noticed as attracting the most people and practices is the one that became equipped with a playground and hence is suggesting the neighbourhood and visitors’ specific modes of use.

A related question was why didn’t we encounter many humans and nonhumans cooling down their bodies under the air-trees? And who are then the urban dwellers that visit this site? Since the Eco-Bulevar is installed in a residential area outside of the city centre, we posit that probably not many visitors accidentally pass by on their urban strolls. Foot and paw prints as well as dog poo indicate that humans and dogs do walk along the Boulevard. But perhaps at other times than a Friday afternoon? In the evenings perhaps? We also wondered about the impact that the air conditioning of indoor spaces might have on the practices of using and appropriating this public cooling infrastructure. Is the Eco-Bulevar not used in the daytime heat, but still functions as a meeting point in the evenings? Wouldn’t it make more sense to install such air conditioning trees in areas with residents with less access to indoor cooling infrastructures? Or better: wouldn’t a moveable version of these cooling trees be a promising option for negotiating urban heat?

After walking along the boulevard of air-trees, we sat down under the last one in two groups to make sense of our feelings, sensations, bodily experiences, and the role played by the various devices brought by participants: water, caps, scarfs, different kinds of fans, sunblock, insulin, water pistols and other devices to sprinkle water, and asthma inhalers. We noticed that the different devices functioned in different ways: for some participants, fans were the most helpful, as they condition the air, providing a little wind and hence making the atmosphere feel a bit cooler. For some, they worked best in combination with a sprinkle of water. Others preferred caps, scarfs, and sunblock, as they protect bodily surfaces from direct sun radiation, even if not having a cooling effect. We then discussed about how we combine different devices and bodily techniques to fend off the heat.

In these group discussions, we came back once more to the issue of what it means for different bodies to be exposed to heat, focusing not only on the cultures or practices of heat adaptation, but also on different heat vulnerabilities and related questions of climate justice and injustice. Which bodies have access to which devices and infrastructures to cool the urban atmospheres that they are enveloped by? How about human urban inhabitants whose homes are not equipped with air conditioning machines or who cannot afford the use of these cooling devices? Or what about those bodies that do not have a private home that can be cooled down and hence are dependent on public air conditioning measures such as parks, other green infrastructures, or cooling centres? What about street workers, moving through dense and hot canyons of asphalt and buildings, or those operating the heavy machinery that constructs these new urban canyons? What about other-than-human living bodies? How do those birds, street dogs, and other urban animals living and dealing with the urban heat islands that they are bound to?

Remembering all the cooling devices that we had come up with, we thought about the inequalities and asymmetries of access to these devices. Do the bodies that contribute to the global rising temperatures the most also get access to the widest range of cooling devices and infrastructures? – such as, for example, us, taking an air-conditioned bus ride during a conference in the South of Europe dealing with politics of technoscientific futures?

Thinking about heat at the ruins of the Escaravox

The Escaravox, the third and last “hot-spot” of our thermodynamic and multimodal ride, was installed in 2012 in the patio of the Matadero, a former slaughterhouse and now a media-arts centre near the river Manzanares. The patio has no trees or any other green infrastructure, just as in many of the plazas and squares of Madrid, but also common in other Spanish and Mediterranean cities. Made as “mobile shading devices” (Jaque/Office for Political Innovation, 2012), the Escaravox consisted of two installations that are reminiscent of the shape of birds with spanned wings, put together with mass-produced and inexpensive fabrics and irrigation structures, and were equipped with sound, lighting, and projection systems. Its materiality reminded us of the shading fabrics used around private houses to shade terraces and balconies. Andrés Jaque, the architect behind the structure, describes them as “infrastructures […] to be available for people to use them, without being invited or curated, through a simple booking process” (Jaque/Office for Political Innovation, 2012).

Ten years later, as we visited the Escaravox, all we encountered was a skeleton, a ruin. Its sight provoked a passionate discussion about what might have happened. For some, the death of the Escaravox was probably a problem of design. If a cooling infrastructure is made of elements that might decay so quickly or require constant maintenance work, then it might should have been designed and/or should have been built differently from the start. For others, the sight of the Escaravox’ ruin was to be read as a sign of a neoliberalizing municipal right-wing politics in Madrid, not only failing to provide resources for the maintenance of public infrastructures, but also attacking cultural centres and spaces, where common-oriented modes of making cities were being reimagined. Apart from these alternative explanations of decay, we discussed a different analysis of the Escaravox, one that complicated the question of when and how shading and cooling infrastructures “succeed” or “fail” their (intended) function.

Indeed, the Escaravox can be understood as having never been planned, designed, fabricated, or maintained to be a long-lasting infrastructure in public urban space, that is to fulfil a permanent function. The Escaravox can be understood as a prototype, that is, a pre-broken artefact that works as a speculative intervention aimed less to function well and reliably than to challenge the way people think about urban spaces, to invite imaginations, and speculations about alternative practices of urbanism. The Escaravox is installed as a shading device on the public patio of one of the most progressive cultural centres of Madrid, but also an important political space. Indeed, the day we visited the Escaravox, a big part of the patio was being used for the launching of the electoral campaign of a Madrid politician running for becoming the new mayor of the city. Hundreds of people, mostly politicians, decision-makers and the media, would gather under the radiant sun with an excellent view on the ruins of the Escaravox in the background. We imagined that even as a ruin the Escaravox might continue to be doing what it was supposed to do: make people think of potential practices and interventions to mitigate the heat in the urban squares and public spaces of cities in the Anthropocene.

What are the futures of heat mitigation in Madrid?

We would like to conclude this report, as we concluded the tour, with a reflection about the future of heat mitigation in Madrid. The question that we think is critical to ask and explore is how each of these interventions not only imagine a future, but also suggest how the present might lead to the future cooling of cities. Bosque Metropolitano is particularly interesting in this regard because it enacts a future far away, a future that most people on the tour or in the city will probably not live to see. The image of Madrid surrounded by a grown and lively forest that cools the city is a dream for the next generation. At the same time, this future is intrinsically connected to the present through the presence of trees. Some of the trees that will be part of that future are already here, with us: we can plant them, water them, and sit under their shade. In other words, the future is not a pure fiction; it already exists in the present albeit at a very small scale and hence it needs to grow. The trees need to grow, the areas for the forest need to expand, multispecies dynamics between planners, trees, and other organisms who will inhabit this urban forest need to flourish. Bosque Metropolitano makes us think about how urban futures can grow from the present and how cultivating an urban forest means also cultivating an urban future. In contrast, the Eco-Bulevar is not enmeshed in a long and slow process of becoming, but it is a fully functioning infrastructure that demonstrates how urban public spaces might need to be designed in the future. Again, the future is already existing in the present, but not as a seed that needs to grow, but rather as an example that needs to be replicated. Indeed, the heat resilient city imagined by the Eco-Bulevar is one in which all major boulevards, squares and plazas might need to have infrastructures similar to the one functioning here. Rather than a process of natural grow, the challenge the Eco-Bulevar poses is one of technological reproduction and replicability. Finally, the Escaravox enacts yet another imagination of an urban future. The Escaravox is neither intended to grow nor intended to be replicated but can rather be seen as an artifact inviting other ways of thinking about the city. Among the three infrastructures we visited, the Escaravox is the only one that does not offer a vision of the future but poses rather a question about what that future might be. The Escaravox disappoints, asks back, provokes, and invites to think with it about the urban futures of heat. It’s the closest we get to Bruno Latour’s Dingpolitik, that is, a thing that summons a public around it.

The event was joined by the film and audio documenting team of Jos Temprano and Victor Rovira, who produced together with the WAVEMATTERS team a video documentation of the event.

The WAVEMATTERS team thanks all participants of the ride for sensing heat, as well as making sense of heat and cooling infrastructures with us!

References and Further Reading

Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 2022. ‘Bosque Metropolitano’. 2022. Estrategia Urbana. DG Planeamiento. Accessed 1st July 2022. https://estrategiaurbana.madrid.es/bosque-metropolitano/.

Ecosistema urbano 2007: eco-boulevard: Accessed 1st July 2022. https://ecosistemaurbano.com/eco-boulevard/.

Interview with Diego García Setién. 17th June 2022.

Andres Jaque/Office for Political Innovation 2012. Escaravox: https://officeforpoliticalinnovation.com/work/escaravox/

Alberto Corsín Jiménez (ed.) 2017: Prototyping Cultures. Art, Science, and Politics in Beta. London/New York: Routledge.